13 November is the Day of the Hungarian Language. On this occasion, we have prepared a short overview of how various exotic animal species—most of which can also be seen in our Zoo—received Hungarian names, even though they originally had none. We also explain why this topic is important for our Zoo.

13 November is the Day of the Hungarian Language, as on this date in 1844 King Ferdinand V ratified Act II of 1844, which made Hungarian the official language of the country. Before that, official matters were conducted in Latin, which was considered the official language of the Kingdom of Hungary.

Today, the official status of the Hungarian language is no longer in question, but preserving its heritage and maintaining and developing the language remain important. This also applies to its technical and scientific registers, including Hungarian scientific terminology.

One special feature of the Hungarian language is that all branches of science can be practiced in Hungarian without particular linguistic difficulties or limitations of vocabulary. This is also true for some other languages, but for far fewer than one might think. Out of the hundreds of languages spoken worldwide, only one or two dozen are truly suitable for expressing all fields of science, and there are many languages spoken by far more people than Hungarian for which this is not the case.

It is true that the international language of science used to be Latin and today is English, but national languages still play an important role in scientific work. Moreover, the language of popular science communication in Hungary should primarily be Hungarian. This means that it is useful not only in science itself, but also in science communication, that the results of all sciences can be expressed in Hungarian.

It should also be noted that this state of the Hungarian language did not develop on its own, but is thanks to scholar-patriots who worked extensively to create and develop Hungarian scientific terminology. In connection with the Hungarian names of exotic animals, the work of János Apáczai Csere, János Földi, Ferenc Pethe, Péter Vajda, Mihály Táncsics, Lajos Kossuth, Lajos Méhelyi and István Chernel was particularly significant.

In our Zoo, communicating natural science and biological knowledge is part of everyday work, primarily in Hungarian (though also in other languages). In this work, we consider the use of clear Hungarian technical language especially important, and we consciously maintain elements of the Hungarian language heritage related to the natural sciences, animals and plants. This also includes researching the origins of vocabulary related to exotic animals, a field in which our experts have long been active.

The Hungarian language’s system of animal names developed over a long period, as a result of several thousand years of evolution. Early occupations such as fishing, hunting and animal husbandry required animal names long before Hungarian existed as an independent language. As a result, common animal names, names indicating age and sex, names for animal groups, and even individual animal proper names may have been present in the language from the very beginning. These names, however, always referred only to animals known to Hungarians and considered important enough in practical terms to merit distinct names.

Accordingly, the names of animals that Hungarians may have known even before the Conquest are usually very old and originate from the Old Hungarian period. For example, the Hungarian word for hedgehog (sün) belongs to the oldest words from the Finno-Ugric period, while the word for horse (ló) dates back to the Ugric era. Interestingly, the Hungarian word for bear (medve) is of Slavic origin, even though Hungarians must have known these animals before Slavic linguistic influences appeared. One possible explanation is that the original Hungarian word for the animal was lost over time due to a taboo on pronouncing its name, and the Slavic-derived term later took its place.

Names for exotic animals also entered the language gradually, as Hungarians became familiar with the animals in question. This process may have begun partly before the Conquest. For example, the Hungarian word for lion (oroszlán) is of Old Turkic origin and probably entered the language through the contacts of early Hungarians with the Khazars. As a result, similar names to oroszlán are mainly found outside Europe, in Turkic, Tatar, Mongolian or Chuvash. In the vast majority of European languages, lions are named using words derived from the Latin leo (such as lion, Löwe, lejon, león, leone, leu, llew, lev, lew, leijona), regardless of whether the language is Germanic, Romance, Celtic, Slavic or Finno-Ugric. In Romance languages this is obvious, while in the others it is simply a consequence of the fact that speakers of Celtic, Germanic, Slavic and Finno-Ugric languages in Europe first learned about the existence of lions from biblical stories known in Latin.

Like oroszlán, the Hungarian word for camel (teve) is also of Old Turkic origin. Its earliest traces appear in Hungarian well before the Ottoman period, making it very likely that it dates back to pre-Conquest times or at least to the Árpád era. It has been proven that Hungarians already knew these animals before the Mongol invasion. The Arabic, and originally Persian, origin of the Hungarian word for monkey (majom) also indicates that it has long been part of the language’s vocabulary.

During the Renaissance and later the Baroque period, Hungarian names for exotic animals were mainly adopted from Latin sources. It is therefore not surprising that the Hungarian words for whale (bálna), elephant (elefánt), hyena (hiéna) and tiger (tigris) are all of Latin origin, or at least entered the language through Latin mediation. Before their spelling became fixed in their modern forms, these words often appeared in Hungarian texts in Latinized forms: for example, bálna was written as balaena and hiéna as hyaena in Hungarian texts of the 17th and 18th centuries. The word strucc (ostrich) is also of Latin origin, originally Greek, but it entered Hungarian via the languages spoken in medieval Italy.

With the development of Hungarian written culture and the influence of the Enlightenment, more and more exotic animals later received Hungarian names. With the appearance of scientifically oriented, systematic works from the turn of the 18th and 19th centuries, it became possible to speak not only of common animal names but also of technical animal terminology, both for native species and for exotic animals. Hungarian-language zoological books of this period presented an increasing number of exotic species. Their authors and translators faced the serious challenge of naming many animals that had previously had no Hungarian names. Some names created by borrowing foreign terms, by literal translation, or by inventing Hungarian names based on the animals’ characteristics later became accepted and widely used, while others did not survive and are now remembered only as curiosities. Contemporary authors and translators experimented with various names for marsupials: some called them tarsolyos, others fiahordó, and still others csecsiszákos (meaning animals that carry their teats in a pouch). The term erszényesek, which was coined in 1841 and remains in use today, is credited to Péter Vajda.

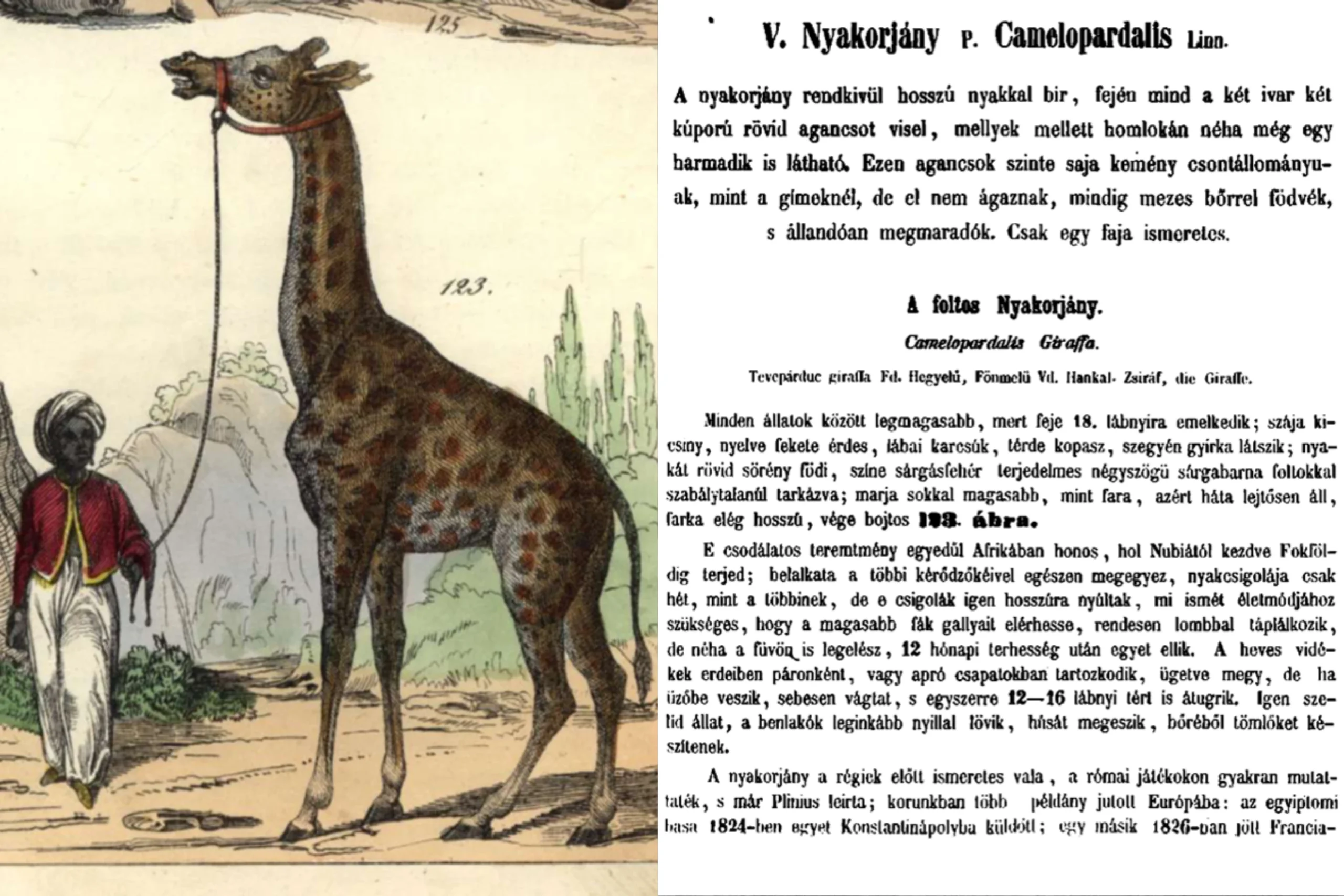

Many unusual animal names were created during this period, especially as a result of a movement that aimed to give every exotic animal an original Hungarian name. For example, the kangaroo, which was already called kenguru in Hungarian by 1801, was instead given the name górugrány, free of foreign origins. The animal known today as the guinea pig (földimalac) was called reményfoki vájláb, and the giraffe was referred to as foltos nyakorján.

This issue did not leave the scientific community indifferent, and a real debate developed over whether every exotic animal should be given an “original” Hungarian name or whether names of foreign origin could also be adopted. This debate was ultimately settled by the authority of Lajos Kossuth. At the time, Kossuth was living in exile in Turin, but he personally took part in this scientific and linguistic discussion. In his article on the Hungarianization of scientific genus and species names, published in 1885 in Természettudományi Közlemények, Kossuth formulated the following position:

“In my view, with regard to those genus and species names for which the various nations of the civilized world do not use one single name in everyday life but different ones, Hungarian may and indeed should create its own name in accordance with the spirit of the language if it does not yet possess one; however, with regard to those genera and species for which the most diverse cultivated languages have accepted the same single word in common usage, whatever its origin may be, Hungarian may also use it without harming the purity of the language.”

This position opened the way for the acceptance of names such as zsiráf (giraffe), kenguru (kangaroo), koala, oposszum (opossum) and vombat (wombat).

After this, what was mainly needed was consistency and uniformity—that is, that authors, translators and all professionals who named animal species in Hungarian for scientific or educational purposes should use the same terms wherever possible. General guidance for this was provided by Hungarian editions of major zoological encyclopedias, such as Alfred Brehm’s multi-volume work The Life of Animals, the first edition of which was published in the early years of the 20th century.