In 1956, major changes took place in our Zoo, although most of these were only partially related to the 1956 Revolution. The battles in Budapest fortunately did not cause major damage, but two hippos died under unclear circumstances.

The year 1956 brought about significant changes in the life of the Budapest Zoo and Botanical Garden. However, these were not so much related to the revolution, and they had already started in March.

Regarding the background, it should be known that the Zoo suffered severe damages during the Second World War, and it was only with great difficulty that it could be reopened and repopulated with animals. The politics of the time did not really support the matter. The renowned Herbert Nadler, who had been the director of the Zoo since 1929, was not acceptable to the communists, and he had also reached retirement age: so, he was sent into retirement (but by the time they would have deported his family, he was no longer alive). Instead, István Láng was appointed as the director, who was actually a shoe upper maker by trade, so he did not possess much of the specialized knowledge that would have been needed at the Zoo and Botanical Garden. But this did not matter, only that he was of worker-peasant origin, and a reliable party member for those in power. Of course, Láng couldn’t do much to change the fate of the Zoo. His successor was not an expert either, but at least he listened to one or two experienced officials of the Zoo who were still in their place.

After the death of Stalin (1953), the easing began and by 1956, in the case of the Zoo, it had reached the point where the maintainer acknowledged that a leader with appropriate expertise would be needed at the helm of the institution. Therefore, on the recommendation of György Hahn, the then head of the Department of Public Education of the Budapest City Council, Csaba Anghi, a scholar of zoology, zookeeping, and animal breeding, was asked to become the director, and later the chief director. Anghi had significant zoo experience, as he led the Mammal Department of the Zoo for years between the two world wars.

Although expertise has finally become a priority, the authorities at this time also expected politically reliable people to lead various companies and institutions. From this perspective, the case of Csaba Anghi is particularly interesting. Indeed, he could hardly be called an authentic communist.

Considering his family background, he came from a Transylvanian Reformed family, his ancestors were Székely mounted nobles (cavalrymen). His father, Ernő Anghi, played an important role in the life and organization of the Reformed Church, and due to his patriotic activities, he was sentenced to death during the time of the Hungarian Soviet Republic, although this sentence was not carried out because the council government fell in the meantime. Csaba Anghi himself often used the noble-origin prefix “szentmiklósi” before the war, and in 1921, as a student of the Agricultural Academy of Mosonmagyaróvár, he participated in the uprising in Western Hungary, during which he was injured (as is known, this uprising led to the fact that, contrary to the provisions of the Treaty of Trianon, Sopron and its surroundings were not annexed to Austria, but the residents decided on the affiliation of the area by referendum).

Therefore, Csaba Anghi was considered “class alien” in terms of his social origin, moreover, he had taken up arms for patriotic reasons many years earlier, which was considered quite suspicious in the communist system. His professional achievements were recognized everywhere, and they could not find anything truly burdensome for him politically. Moreover, Anghi has already helped many people belonging to the working class during the period between the two world wars. People living in the vicinity, often under very tight financial circumstances, regularly visited his house in Pestszentlőrinc for advice, who tried to improve their situation by breeding rabbits, poultry, or other small animals.

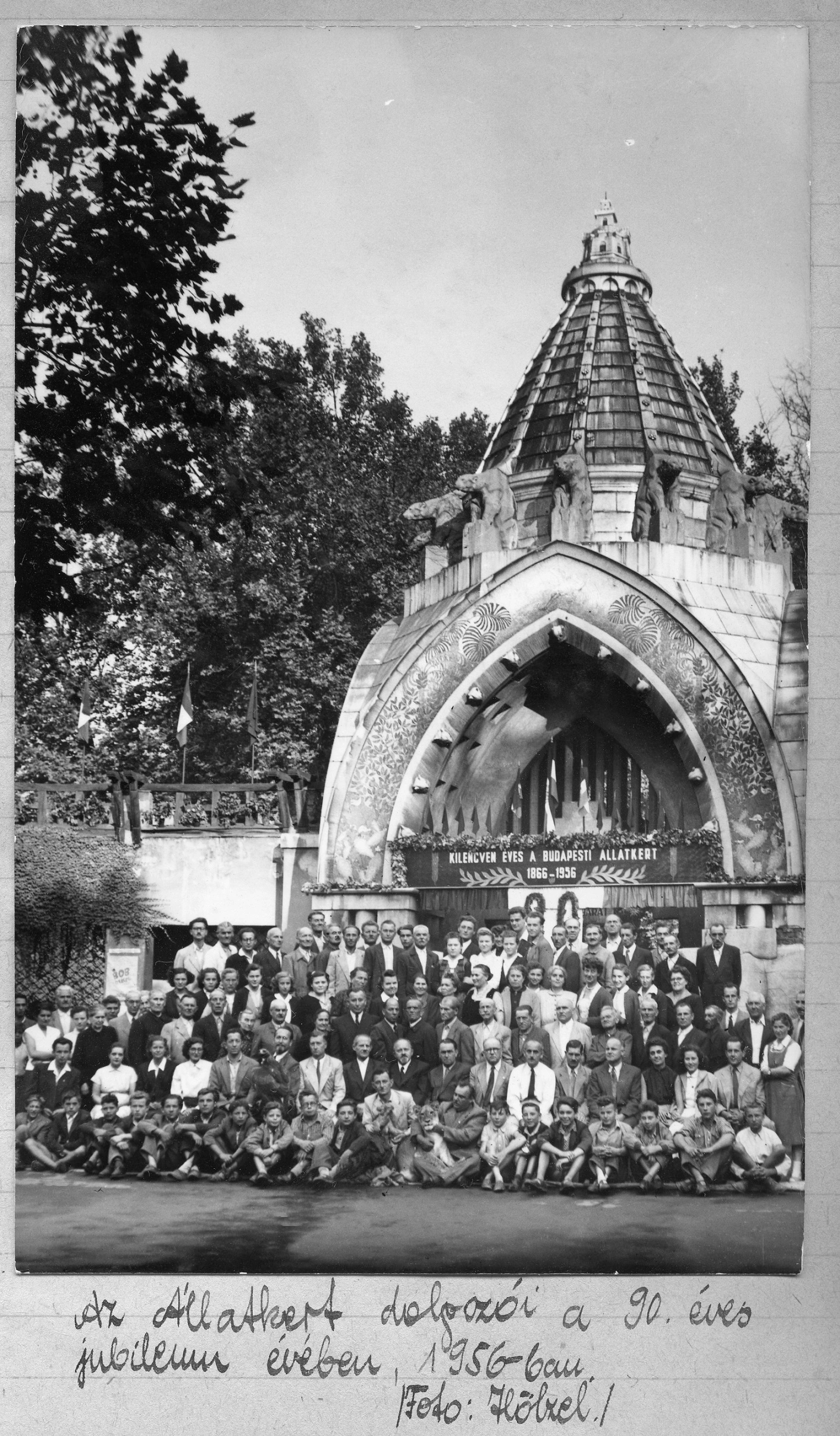

So, in March 1956, Csaba Anghi took over the leadership of the Zoo, which from then on finally began to operate on a professional basis. There were many tasks to solve, so only minor changes could be achieved in a few months, but in August, the employees could celebrate the Zoo’s 90th birthday in a particularly optimistic spirit. For the notable anniversary, the Zoo prepared an exhibition about its past, present and future. The exhibition was located in a building, which was used as a bird shelter at the time, and is now known as the Xántus János House. During the year, the audience could rejoice at several important offspring, among which the most important was the birth of a baby elephant. The elephant – since it was born in the 90th anniversary year – was named Jubile. Similarly, the arrival of the Southern hairy-nosed wombat was a great sensation, as even back then, wombats were kept in very few zoos outside of Australia.

During the revolution that began on October 23, 1956 the Zoo and Botanical Garden was temporarily closed. Behind the closed gates, of course, the work continued, as the animals had to be taken care of regardless. Fortunately, the most experienced workers lived on-site, in the service apartments of the residential building located in the economic courtyard, which mattered a lot, because public transportation (“Beszkárt”) was temporarily shut down. There were some issues with the feed supply, but they managed to solve this problem as well. And fortunately, the battles taking place in Budapest barely affected the Zoo. No serious damage was done to the buildings, although there were losses in the animal population. For example, two ostriches got very scared, and in their panic, they even hurt themselves. With that said, the extent of the damage could not even be compared to the devastation of the war eleven years earlier.

The case of the two hippos, Csöpi and Bobby, who perished during the time of the revolution, is indeed mysterious. Opinions are divided about the circumstances of their death. In a speech addressed to the garden’s staff prior to the reopening after the revolution, Anghi Csaba, whose text has been preserved in the Zoo’s yearbook, mentions the death of the two hippos as a great loss (in fact, it was three, because Csöpi was pregnant). The text does not elaborate on the specific reasons, but refers to employee responsibility. According to some opinions, the cause of the animals’ demise was due to feeding-related harm, but among the older workers, there was still a rumour in the 1980s that the hippos had actually “boiled” because when filling their pool, the tap for the thermal water was opened, but the cold water was forgotten. According to the latter story, the operation was not performed by the experienced hippo keeper, because he could not get to the Zoo, but by someone who was temporarily assigned there.

Today, it is hard to say whether things really happened this way, but one thing is certain, that the Zoo’s staff, as far as their possibilities allowed, did their job during this period as well. Of course, discipline was occasionally relaxed here and there, which Anghi also mentioned in his speech, but under the given circumstances, he rather classified this as “childish mischief” than a serious violation.

The revolution, as we know, was suppressed, and then the reprisals also began. In the Zoo, initially, it was only noticeable that, due to higher orders, ideological lectures had to be held for the workers with the aim of supposedly counterbalancing “the ideological damage of the counter-revolution”. That is, they told what to think about the matter. These “further trainings” were organized by Deputy Director György Domán at the Zoo and Botanical Garden. In addition, there were also personnel changes. Partly because some of the middle managers of the Zoo emigrated after 1956. For example, József Somogyi, the horticultural director, continued his career in Sweden, while Lóránt Bástyai, the head of the Bird Department, continued his career in England. Márton Wiesinger, the head of the Aquarium-Terrarium Department, stayed at home, but was not allowed to continue working at the Zoo, so he continued his career as a high school teacher. Fortunately, Anghi was given pretty much free rein to fill the vacant positions, so experts could be placed everywhere. The new head of the Botanical Department is Mária Kiáczné Sulyok, the Aquarium-Terrarium Department is led by Bethlen Pénzes, and the Bird Department is now headed by Tamás Fodor.